I could not get a bead on Act 1, but I found Act 2 rewarding, which sucks, I guess, for the people who left at intermission.

In the theatre, style is often the trickiest thing to get right, and this script exists in a stylistic hall of mirrors. Henrik Ibsen, who wrote A Doll’s House, which premiered in 1879, is often called the father of theatrical realism. But he was heavily influenced by melodrama, the style from which his work emerged, so it’s mistake to perform his plays too realistically.

Playwright Amy Herzog’s adaptation of A Doll’s House, which we’re seeing here, smooths out the baroque language you’ll find in most translations of the Norwegian’s scripts, making the dialogue sleekly modern and naturalistic. Still, the story’s melodrama — its coincidences, high stakes, and huge emotions — must be accommodated.

In the story, Nora Helmer is the bourgeois wife of Torvald, a newly appointed bank manager. Trapped by gender norms, Nora finds power using the tools available to her. With her husband and friends, she is coy, manipulative, selfish — and sometimes brave. But she has made a tactical error: unbeknownst to her husband, early in their marriage, she financed a trip to Italy, which was lifesaving for Torvald, by getting a loan — and she forged her father’s signature to do so. Nora committed fraud. And now Krogstad, the loan shark, who works at Torvald’s bank, is blackmailing her to use her influence to secure his position.

Spoiler alert.

Fearing shame and rejection, terrified that her lies are morally poisoning her children, Nora is driven to the brink of suicide before coming to the realization that self-actualization — not duty to her husband and kids — is her primary responsibility. In a decision that was revolutionary when the play premiered, and that keeps it startlingly relevant, Nora walks out on her family, with no promise to return.

Narratively and thematically, this is big stuff. And director Anita Rochon’s production embraces grand gestures.

Amir Ofek’s drawing-room set is pale blue, vast — and empty, its one piece of furniture a pale pink sofa so big it could have come from a giant’s castle. Every time a character is introduced, their arrival is marked by a blackout, a blinding flash, and a thunderclap. When Nora goes nuts — and she goes pretty nuts — she climbs all over that sofa like a wild thing.

So there’s melodrama but, in Act 1, the tension between melodrama and realism doesn’t feel stylistically resolved. The set, which seems to be a commentary on the emptiness — even theatricality — of Nora’s life, also feels theatrically vacant, much like the relationships between the characters in this production.

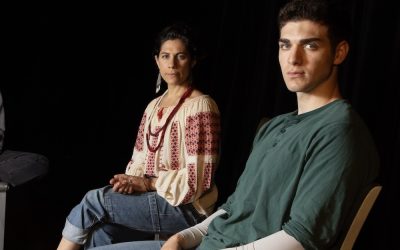

The lynchpin, of course, is Nora and, although I admired actor Alexandra Lainfiesta’s emotional agility — she flips from tone to tone with alacrity and sincerity — I didn’t get the impression that her Nora was very skilled in the performance of her life or that she embraced its conventions. Many of us, I’m sure, have the sense that we’re performing our lives at times, but we’re committed to the gig, if you know what I mean: there’s consistency to what we’re doing and we’re good at “being ourselves.” But the seams are showing in Lainfiesta’s Nora: her attitudes and strategies are obvious. When she flaunts her good fortune in front her financially desperate friend Kristine Linde, for instance, there isn’t a whiff of the charm that could make that moment less crude. And she seems to find scant pleasure in being Torvald’s “little bird.” Who, exactly, is she trying to be and why is she so bad at it? If Nora is this disjointed and transparent, why does anybody put up with her, never mind like her?

To be clear, I’m not saying that the characteristics Lainfiesta and her director Rochon have chosen to highlight aren’t there in the text. Intellectually, the choices make sense, but they also feel abstract, more like illustrations of a thesis than elements of a compellingly human characterization.

All this said, Lainfiesta’s transformation in the second act is remarkable. In the climax, when Nora sees who Torvald really is, you can’t help but feel the impact in your own body. Lainfiesta’s voice drops, her gaze steadies. As I’ve been saying, Nora has been out of focus, but, when she comes into focus, I can’t deny that there’s a pay-off.

Throughout the evening, I also appreciated other characterizations: the groundedness of Carmela Sison’s Kristine, the successfully melodramatic complexity of Ron Pedersen’s Krogstad, the wariness of Marcus Youssef’s portrait of family friend, Dr. Rank. Playing Torvald, Daniel Briere embodies the character’s smug self-satisfaction, and leavens it with charm.

Narda McCarroll is responsible for the dramatic lighting, which includes everything from glaring fluorescents to expressionistic shadows. Sound designer and composer Malcolm Dow contributes a persuasive and cinematic score.

This production didn’t always work for me. More importantly, it challenged me to think and I appreciate its ambition.

A DOLL’S HOUSE by Henrik Ibsen, adapted by Amy Herzog. Directed by Anita Rochon. This Arts Club/Theatre Calgary coproduction is running at the Stanley BFL Canada Stage until October 5. Tickets and information

PHOTO CREDIT: (Photo of Alexandra Lainfiesta and Daniel Briere by Moonrider Productions)

THERE’S MORE! You can get all my current reviews PLUS curated local, national, and international arts coverage in your inbox FREE every week if you subscribe to Fresh Sheet, the Newsletter. Just click that link. (Unsubscribe at any time. Super easy. No hard feelings.) Check it out.

0 Comments